An essay on nuclear war and the film. Don’t worry, NO spoilers.

UPDATE: On early Thursday morning, minutes before meeting President Xi Jinping of China in Asia, Trump announced the U.S. would resume testing nuclear weapons.

“Because of other countries testing programs, I have instructed the Department of War to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis,” Trump wrote on Truth Social.

When we published this essay a week ago, we knew the issue was important; what we didn’t realize was how timely it would become. The U.S. has not tested a nuclear weapon in 33 years.

Our original essay continues below.

Thirty minutes.

Thirty.

That’s roughly how long it would take for an ICBM carrying a nuclear warhead to travel from Russia or North Korea to the continental United States.

In thirty minutes, everything you ever understood to be true, everything you ever understood to be real would not just change.

It would vanish.

Vaporize into a cloud of radioactive dust.

If launched from a nuclear submarine or bomber, it’s all over in less time than a Seinfeld episode.

There are an estimated 12,300 nuclear warheads in the world.2 About a third are deployed—meaning they are sitting on a missile or at a bomber base.

Of the world’s inventory, roughly 4,900 warheads are in the hands of Russia, China, or North Korea.

For perspective, the U.S. Missile Defense Agency has 44 ground-based interceptors meant to stop an incoming ICBM from hitting the homeland.

Their success rate? A little more than a coin toss.

About 2,100 warheads are on “high alert” around the world, meaning ready for use on short notice. Studies show that only a few hundred detonations are needed to cause a Nuclear Winter.

At least one study put that number as low as 100.

“We all built a house filled with dynamite, making all these bombs and all these plans. And the walls are just ready to blow, but we kept on living in it.” — POTUS, A House of Dynamite

Have we begun to neglect this existential threat?

Katheryn Bigelow’s latest movie, “A House of Dynamite,” seems to consider that question—and then attempts to rattle us awake. Twenty minutes is the timeframe given in the film, shorter than what some experts say about a land launch by most of America’s adversaries, but well within the realm of possibility. Bigelow makes you feel how short 20 minutes really is and how little can be done.

When Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer hit theaters in the summer of 2023, I was enamored by the epic story, and yet part of me couldn’t help but feel its warning about nuclear apocalypse was…quaint, old.

“Oh Chris, you’re 30+ years too late on this morality tale. Everybody knows this,” I felt in a certain corner of my soul. “What a wonderful film. But this lesson, dear director, is old hat.”

I knew—logically, politically, spiritually, obviously—that this odd feeling was incorrect. I knew the threat was as real today as it was on Oct. 16, 1962, when Cuba picked up Russia’s gun and held it to our head. Since 1950, there have been at least 15 nuclear close calls,3 moments where hundreds of thousands of people could have been killed if not for a certain amount of heroism—and luck. (And those are only the incidents researchers are aware of.)

Yet, I also knew the feeling—that visceral dismissal—carried weight. It held a slice of truth: We had lulled ourselves into complacency.

This essay is part of a new series called The 2030 Peace: Sign up here.

We’ve somehow come to believe the risk has passed. Because we survived the Cold War, because we survived conflicts like Vietnam, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, because a nuclear war hasn’t happened yet, we somehow believe we’re in the clear. If it hasn’t happened yet, well surely, we must have figured it out. Surely, we’ve done our job in warning the world; people understand this threat and take it seriously; mission accomplished. Surely, we must be in control.

Today, if you were to ask people about what threats concern them, nuclear war would fall far down the list—if it were mentioned at all without prompting. Climate change, global pandemics, mass shootings, the rise of authoritarianism, political division, immigration, and crime all poll higher on voters’ lists of concerns. In a survey conducted a few years ago, 39% of respondents said they did not worry about nuclear catastrophes of any kind.3

To an extent, this is understandable. We feel the effects of climate change grow worse and worse year after year. We have experienced the terror of a global pandemic. Our headlines are filled with mass shootings and political crises. Propaganda spilled out all over the internet revolves around immigration and crime, meant to keep us divided and fearful. Those are the issues we consume in the media of our day-to-day lives, and therefore those are our realities. Meanwhile, nuclear testing has moved away from destroying islands in paradise to underground, away from eyes and cameras. Nukes have been pushed off the page and off the stage.

For much of the 20th century, nuclear annihilation was our greatest fear—for obvious reasons. The world had just seen the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Videos disseminated to the public showed ever bigger and stronger bombs detonated in the South Pacific—explosions that not only wiped out islands, they erased them like sand castles. Meanwhile, the world’s two largest superpowers, the USA and USSR, were amidst the fever pitch of the Cold War.

The nuclear threat was very real and present in people’s lived experience. School kids practiced bombing drills—hide under your desk, Johnny, and kiss your ass goodbye. Parents remembered the Cuban Missile Crisis, when for 13 days, Earth sat at the brink of apocalypse. Activists and scientists and politicians and journalists all put the nuclear problem at the forefront of the discussion—on front pages and lecture podiums.

Hollywood played a major role in the public’s processing of our newfound nuclear capability. Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) leaned into the comedic absurdity of this self-imposed doomsday and the existential dread it dredged up in us. (The rest of the movie title is “or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”)

Major TJ “King” Kong rides a nuclear warhead in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

The Day After (1983) depicted what a nuclear strike would feel like in middle America. Much of the action takes place in Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas City. The TV movie shook the American zeitgeist and is credited with shifting public policy on nuclear weapons towards restraint. Pres. Ronald Reagan screened the film at Camp David a month before its national broadcast, later writing in his diary it was “very effective & left me greatly depressed.”4

That era of awareness has since passed. Bigelow’s film is keen on reviving it.

A House of Dynamite

Nolan’s virtuosic final frames of Oppenheimer embedded themselves into my DNA, both in their artistry and existential alarm. However, for all of the film’s philosophical mastery, audiences are able to wriggle out of its morality tale.

Movies like Oppenheimer and Thirteen Days—a harrowing play-by-play of the Kennedy administration’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis—are period pieces. Their beauty and nostalgia are part of their charm; it’s also what makes them distant. It allows the audience to put their existential fear at arm’s length. ‘This all happened so long ago, in another time.’

The Day After came out in 1983 and took place in 1983. House of Dynamite takes place in the 21st century—in what appears to be an Obama-like administration. The audience cannot avoid the applicability. The films scream, ‘This could happen now, and this is what it would look like.’

Check out this neat ‘Minute-by-Minute Watch Guide’ for A House of Dynamite from the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. (It contains spoilers.)

Both start in the middle of everyone’s typical ho-hum life: people going to work, catching mass transit, driving, ordering cheap egg sandwiches. Bigelow depicts the crisis in an (almost depressingly) relatable way.

People on iPhones miss important phone calls, have ill-timed conflicts with loved ones, and scroll through photos in passing moments.

The president’s smartest people are befuddled when they can’t merge a critically important phone call in a conference room. (We’ve all been there.)

A national security expert struggles to get through basic security while on the most important video call of his (perhaps soon-to-be-short) life. That sequence is so anti-cinematic that it’s aesthetically annoying—and yet terrifying. The scene is almost comedic in its realistic absurdity, except any laugh would be simple self-defense against the movie’s most uncomfortable reality.

We are not in control.

The illusory nature of control

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men might fail to save the world from apocalypse not because they are evil or incompetent, but because they are still cursed by the mundane, by the basic nature of human fallibility.

Nuclear annihilation does not care if your mic is muted.

This lends itself to a core lesson of the film: No one and no group is ever fully in control. And when that reality collides with nuclear weapons—for all our expertise and all our preparation and all our protocols—we are, at best, gambling with oblivion.

“I always thought… just being ready is the point, right? Keeps people in check. Keeps the world straight. If they see how prepared we are, no one starts a nuclear war, right?

It’s insanity.” — POTUS, A House of Dynamite

Whereas Oppenheimer is very much a retelling of Dr. Frankenstein, as ‘Oppy’ comes to terms with the monster he’s created, House of Dynamite deals less with creation—since we are now indeed 80 years on—and more with the illusory nature of control, mankind’s greatest self-deception.

In this way, House of Dynamite exists not just in conversation with other nuclear war films but also with another Frankenstein retelling: Jurassic Park. Dennis Nedry is a more typical Hollywood villain, yes. But his eye-rolling (and depressing) slobbishness is another example of how mundane human error can be. “Dennis, our lives are in your hands, and you have butterfingers?” exclaims genius billionaire John Hammond, the film’s Dr. Frankenstein.

All three films come to the conclusion that some creations are so big—so monstrous—no amount of human ingenuity can bring them to bear, not all the technology and power and genius money can buy. “We spared no expense!”

Remembering Petticoat Lane, Jurassic Park

“You never had control! That’s the illusion!” — Dr. Ellie Sattler, Jurassic Park.

Much of the rationale for nuclear buildup is deterrence—MAD: mutually assured destruction, the premise that no one will fire a nuke if they know doing so would result in nuclear retaliation. The concept relies on controlled behavior, on rational actors doing what’s best for self-preservation.

But one of the world’s top researchers on nuclear proliferation, Professor Benoît Pelopidas, points out a striking paradox: a key component of nuclear deterrence is not control but a catastrophic measure of irrationality. Any nuclear-armed nation would not survive more than a dozen nuclear strikes. For Great Britain, France, and Israel, the number is quite small. Any nuclear first strike would likely involve more than the threshold for total national annihilation. Meaning, the attacked nation’s nuclear response under MAD would not be based on survival or self-preservation, but on vengeance.

“For the whole edifice of nuclear deterrence to logically make sense, the driver has to be and would be anger—not rationality.” — Professor Benoît Pelopidas

We’ve had these weapons for less than a century. The Trinity test occurred July 16, 1945. There are countless people older than the atom bomb. In the grand scheme of history, nukes were invented this morning. If we were to fall into a nuclear holocaust now, future historians presenting the long arc of human history would consider the bomb having been created on a Monday morning and humanity ending by mid-afternoon. We have not yet seen Tuesday.

The further irony of having avoided calamity for 80 years is the illusion that we’ve avoided nuclear war by sheer will.

“It’s crucial that we distinguish whether we’ve avoided unwanted nuclear explosions because we’ve controlled everything—or whether we’ve avoided it thanks to other dimensions,” Professor Pelopidas, who published Rethinking Nuclear Choices in 2022, explained during a podcast that year. “The other dimensions are modes of luck.”

House of Dynamite does a great job of illustrating this variable of fortune. In a more powerful moment of the film, a soldier cries out, “We did everything right!” in the face of failure.

Reality is even more sobering.

Nuclear Modes of Luck

Of the near-catastrophic incidents researchers are aware of, Pelopidas spells out those modes of luck.

1️⃣ Fortunate Failures in Control.

Ironically, we have avoided nuclear disaster due to moments where we did not follow controlled practices. Including:

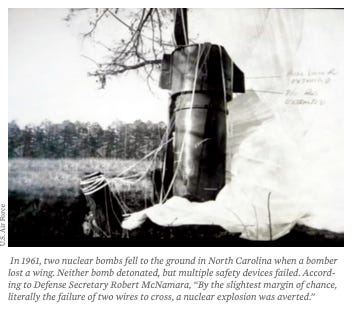

a) Failures in technology.

Literally, something didn’t work—or didn’t detonate—like it was supposed to, avoiding tragedy.

b) Failures in the chain of command—meaning somebody disobeyed.

Pelopidas lays out what I consider to be the most terrifying nuclear paradox. In practice, proponents of nuclear deterrence do not have full and consistent trust in the leader (president, chancellor, etc.) to make the right decisions. What they trust is the rationality of the chain of command in the aggregate. They believe that in the face of a “crazy,” illegal, or illegitimate order, “someone down the chain of command will recognize it for what it is and will disobey.”

This is a dangerous contradiction because these organizations—governments, militaries—are based on an ethos of total control where every member down the chain of command is trained to obey orders. But when it comes to nuclear risk, according to Pelopidas, there’s an underlying expectation that someone will disobey.

“What I call fortuitous disobedience,” Pelopidas said.

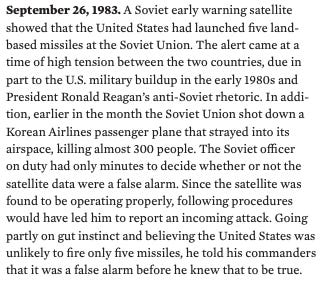

An example of “Fortuitous disobedience” where a false alarm turned out to be the sun reflecting off the tops of clouds. And other examples of control failures.

2️⃣ Factors independent of control

Like the weather.

In 1980, an engine on a B-52 bomber at the Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota caught fire. The blaze lasted three hours despite efforts by firefighters, and the main factor that kept the flames away from nearby armed SRAMs (Short-Range Attack Missiles with nuclear warheads) was the wind.

3️⃣ Resilience despite failure of control

These are moments when we avoided disaster even though a failure of control had led to near calamity. I call this a mix of human fortitude and good luck, which involves a measure of consistency and control in the hopes that a chance opportunity might come your way, allowing for a change in outcome.

You remain ready for luck to swing in your direction. But what happens when luck runs out?

89 Seconds to Midnight

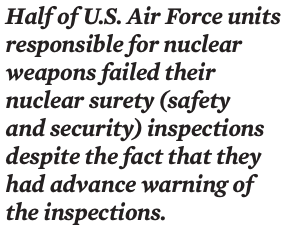

We can clearly see how precarious and dangerous this all is; we can see the amount of luck needed even when we’re lucky enough to have the best people running the world’s largest nuclear arsenal.

And we all know that is no longer the case anymore.

In a world with rising authoritarianism and fascism, increasing divisions and violence, eroding democratic institutions and more unpredictable actors, nonproliferation must be at the forefront of our political movements.

The persistent danger these weapons pose is unsustainable.

The dangers of an unstable U.S. president.

Additionally, the cost to prop up this system of doomsday spirals when you include the apparatus meant to build, secure, maintain, and deploy it. All of those resources could move away from threatening Nuclear Winter and toward helping millions of Americans with healthcare, education, and basic necessities—not to mention the billions of citizens that would stand to benefit in the eight other nuclear powers.

The worldwide system of so-called nuclear deterrence erodes liberty and places every human life in the path of a dangerous set of dominoes. The world cannot be free under the existential threat of a global killer.

The cost of maintaining this house of dynamite is unacceptable. The cost of igniting this house of dynamite is unthinkable.

In 1945, Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and scientists at the University of Chicago who worked on the Manhattan Project founded The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. Two years later, the group created the Doomsday Clock, an assessment of our risk of global catastrophe due to manmade technology, with “midnight” symbolizing apocalypse. Every year the group publishes the clock as a threat-level warning, with recent concerns revolving around nuclear war, climate change, and artificial intelligence.

In 2025, the Doomsday Clock was set to 89 seconds to midnight—indicating the closest we’ve ever been to oblivion.

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of our new series, The 2030 Peace. In the project and book we’ll discuss what increases the risk of conflict, how we avoid war, and how we create lasting conditions for peace. Please join us: Sign up here.

I had a weird takeaway from the movie.

My first thought was, wouldn't it be nice to have an Idris Elba type as president handling that crisis? We have in the past. Why did we allow such incompetence to preside over this?

But Bigelow's point seemed to be that it doesn't matter. Whether the president is a sociopathic buffoon or someone with empathy and intelligence, the whole ball of mud (a well-known topic in the software world) is out of our hands, simply because the technical web of it all is out of our hands. Once a certain event takes place, and we can't know in advance what that might be, there's no way to stop the top from spinning off the table.

I was not as enamored of the movie as you were. I felt like it was a little flat, although Elba is always good. But there was one very powerful scene involving the DOD chief that I won't give away here. That alone made the movie memorable for me.

Where has all of our knowledge and progress, accumulated over the past 10,000 years, taken us?

We have created weapons of mass destruction that will wipe out all humanity. We have destroyed our natural environment to the point of extinction. We are able to deploy biochemical weapons that will unalive everyone except bacteria. We have developed AI technology and when AGI is achieved everyone dies.

On our way to one or all of these catastrophic end of life scenarios, we developed AI and mass surveillance capabilities with energy and water intensive data/cloud centers under the control of fascist, oligarchic, theocratic ethno nationalist regimes to control the masses for a very short time before the fireworks go off and the greed addicts, control freaks, power hungry criminals and psychopaths that accelerated our demise run to their apocalyptic luxury bunkers and enjoy watching on their big screen TVs, the carefully planned demolition of the human species, all animal life, societies and everything else along the way.